The Picasso mystery

Three months ago an elderly couple turned up at the office of Picasso's son with a haul of lost works, triggering a police investigation. Kim Willsher reports on an unfolding drama

Claude Picasso knows an original Picasso masterpiece when he sees one. As the only surviving son of the 20th century's greatest artist and the self-anointed defender of Pablo Picasso's name and legacy, he has spent almost four decades waging war on the forgeries, fakes and general tat attributed to the art world's first modern superstar.

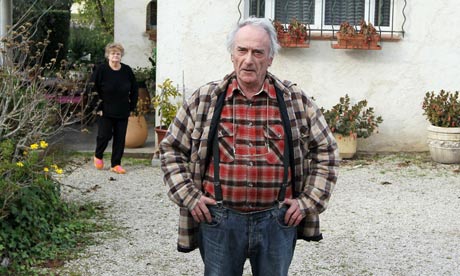

So when retired electrician Pierre Le Guennec and his wife Danielle arrived at his Paris office claiming to have works by "the master", he was ready to deliver a polite but firm brush-off.

The extraordinary story of this treasure trove of previously unseen works by Picasso began at the start this year. On 14 January a letter arrived at the Picasso Administration, which represents the artist's heirs. It contained 26 photographs of dubious quality purporting to be of works by Pablo Picasso and a request that they be authenticated. In March a second envelope arrived with another 39 photographs, followed by 30 more pictures in April.

Finding no references to anything matching the photographs in the inventory of Picasso's work or the inventory compiled after his death, Claude Picasso, who heads the Picasso Administration, wrote back saying he could not issue certificates of authenticity for what were clearly reproductions. The couple replied, more insistent, and were invited to bring the works to Paris to meet Claude.

So one day in September, the couple, in their 70s, stepped timidly into his offices in the Opéra district of Paris. Nothing marked them out from the ordinary. "The man was wearing an old-fashioned suit and a tie," Christine Pinault, Claude Picasso's personal assistant, told the Guardian. "His wife had made an effort with her hair and makeup, and polished her nails, but you'd have passed them in the street without giving them a second glance. You'd never have guessed what they had with them, which is probably just as well."

After hands were shaken and bonjours exchanged, Pierre Le Guennec, 71, opened the black, wheeled suitcase he had trundled noisily across the parquet floor and pulled out drawings, paintings, sketches and lithographs and placed them carefully on a table. As he produced sketchbooks and fragile, but apparently undamaged, papers from the case, Picasso and Pinault – who with the Le Guennecs were the only people present in the room – each drew a silent breath. This unremarkable couple had travelled by TGV from their home in the Côte d'Azur and across Paris by public transport carrying tens of millions of pounds' worth of original Picasso work, much of which had not been known to exist and which had been hidden for nearly 40 years.

"M Le Guennec opened the case and took the pieces out," said Pinault. "One after the other there they were on the table; we were bowled over to see so many unknown works of such great quality. It was an emotional moment. M Picasso went quiet. There was an atmosphere of stupefaction."

Among the collection, dating from 1900 to 1932, was a painting from Picasso's celebrated blue period, along with nine extraordinary cubist collages described as "painted proverbs" and thought to have been lost.

Claude, 63, the artist's third child, could hardly believe what he was seeing. He was immediately suspicious. The unique numbering system used by Picasso and found on the artwork proved they were original, but the lack of dating or dedication and the sheer number of pieces threw doubt on Le Guennec's story that he had been given the works as a gift. "Pablo Picasso was generous," said Claude. "But he always signed and dedicated his gifts even when he knew that people would sell them because they needed the money.

"To have given such a large quantity of work ... it's never been known and to be honest it doesn't stand up."

He pointed out that Picasso, who rose from penniless Spanish immigrant to one of France's most revered adopted sons, was notoriously reluctant to part with his works, even after they had been sold. In later life he went as far as to bid at auctions to buy them back. He was also aware of his own importance in the history of art and the value of even a hurried scribble on a train ticket.

It took three hours to go through the contents of the suitcase of 175 individual works before Claude and his assistant let the couple leave, taking their suitcase – by now repacked with the valuable oeuvres – with them. It was a remarkable display of sang froid.

"M Picasso told the couple the works were interesting and that he would do some research and consider their case and would contact them. He didn't want to alert them that he knew what they had," Pinault said. "We knew we had to let them leave but it was hard and we were worried. We kept thinking, 'What if something happens to the works?'"

After ushering Le Guennec and his wife out of the door, Claude Picasso called Jean-Jacques Neuer, the Picasso family lawyer, who contacted the police. On 5 October, investigators swooped on the couple's modest family home in Mouans-Sartoux in the Alpes Maritimes of southern France and seized a treasure trove of 271 original Picasso works worth an estimated €60m (£50m). At the same time Neuer began legal action against "unnamed persons" for receiving stolen goods, a French legal move allowing police and magistrates to investigate possible suspects.

Pierre Le Guennec, who was taken into custody and released, told police he had been given the works of art by Picasso and his second wife, Jacqueline Roque, after installing burglar alarms in the artist's homes including La Californie in Cannes, the Chateau de Vauvenargues and the mill at Notre Dame de Vie in Mougins, where Picasso died.

In the years that Claude – a former Vogue photographer – has managed his father's estate, he has discovered that Picasso was telling the truth when he announced, shortly before he died intestate, that the squabble over his inheritance would be "much worse than you can imagine". Though an artistic genius, Picasso was deeply flawed in his human relations, wilfully sowing discord among his family to the point of cruelty. Sorting out his legacy was never going to be easy.

He died on 8 April 1973 while he and Roque were entertaining friends at their home. "Drink to me, drink to my health. You know I can't drink any more," were the artist's reported last words. He left four children: Paulo, who was the only legitimate child, born to his first wife, the Russian ballerina Olga Khokhlova; Maya, born to his mistress Marie-Thérèse Walter, and Claude and Paloma, born to his mistress Françoise Gilot.

While Claude has spent much of his life being a gatekeeper to his father's work, strictly controlling copyrights and use of the family name, his zeal for protecting the Picasso name may be explained by the battle he had to be recognised as Picasso's legitimate heir. In 1961 Picasso married Roque, reportedly to spite Gilot, who had hoped to marry the artist and have Claude and Paloma recognised. Then when he died, Roque attempted to prevent his children and grandchildren inheriting anything, resulting in a lengthy battle for his estate. Roque took her own life in 1986.

Given the rivalries between his wives and mistresses, a dispute between their children was almost inevitable. "You can never get two members of the family to agree on anything," Claude admitted as he struggled to broker a deal between the warring relatives.

Both Claude and Paloma were estranged from their father at the time of his death. When Gilot wrote a book about her turbulent relationship with the painter, Picasso disowned her and both their children. After he died Claude and Paloma applied to the French courts for recognition as his descendants and heirs. A legal ruling was made allowing them to adopt his surname. "I wish you were dead," he is reported to have told Claude the last time he saw his son.

In the years that followed, an uneasy truce was brokered, but the family continues to fall out at regular intervals. In 1999, Claude allowed French carmakers Citroën to use Picasso's name and signature for their Xsara model. Picasso's granddaughter Marina accused Claude of abusing his power as director of the Picasso Administration. "I cannot tolerate the name of my grandfather being used to sell something so banal as a car," she told French journalists. She was backed by the celebrated photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson, a friend of Picasso, who wrote to Claude upbraiding him for a shameful lack of respect for "one of the greatest painters, a genius".

Following the recent discovery of unseen Picasso works, family members have remained uncharacteristically quiet. Meanwhile, Le Guennec is sticking to his story. "One day [Picasso] suggested I have tea with him," he told Nice-Matin newspaper. "He just wanted to know what I did, how I was, simple things like that. From then on tea with the master became something of a ritual.

"One evening when I was ready to leave their home, Madame [Roque] called me. She gave me a box of drawings and said, 'It's for you'. I was embarrassed, but when people accuse me of theft they forget that to leave his house every day I had to pass his secretary's office and at the entrance of the property there were always two guards."

In his Paris chambers, Neuer cannot disguise his scepticism over the story. "Frankly it is absurd, out of this world. If you'd been given that many Picasso works, wouldn't you have put one or two on the wall? And if you are hard up as this couple appear to be, wouldn't you have sold at least one in the last 40 years to make ends meet?

"Picasso kept copious notes and diaries of his life and yet nowhere is M Le Guennec mentioned as a friend. And yet he gives him not one, not two, but 271 works of art. Does this sound likely? We have to wait for the police to finish their inquiry, but what can I say: I think not."

This article is from: http://www.guardian.co.uk/artanddesign/2010/dec/04/picasso-unseen-works-mystery

No comments:

Post a Comment